By Joseph Rose | The Oregonian/OregonLive

on April 19, 2016 at 10:50 AM, updated April 19, 2016 at 4:47 PM

Talk about interesting (and spooky) timing.

In a matter of a few days, a series of deadly earthquakes hit Japan and Ecuador, and New Yorker writer Kathryn Schulz won a Pulitzer for "The Really Big One," her brilliant disaster-movie-like narrative of what awaits those of us living along the Cascadia subduction zone.

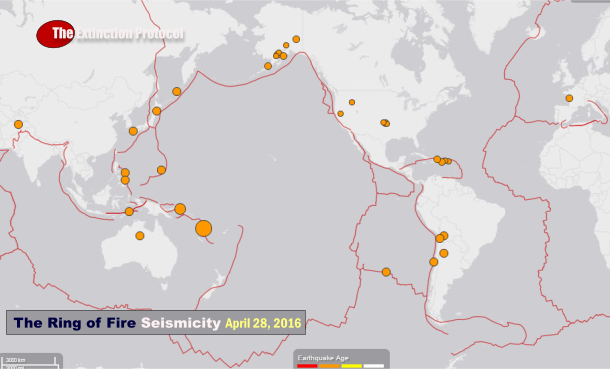

Which begs the question: Should people living in the Northwest be worried that the weekend's catastrophic Ecuador and Japan quakes – hitting magnitudes of 7.8 and 7.3, respectively – are a harbinger for the inevitable death, destruction and tsunamis that awaits us someday?

The countries are, after all, located on both sides of the Pacific Ocean. Are the ocean's tectonic plates shifting? Are the recent earthquakes connected? Good lord! Could we be next?

Take a deep breath, says Jeroen Ritsema, a professor of geophysics at the University of Michigan.

"There's no reason to believe they're related," Ritsema told Slate. "Sometimes earthquakes are closely clustered. Sometimes they're not."

Even when they occur back to back, he told the online news site, they aren't necessarily caused by each other. In fact, he said, the latest quakes involved completely different tectonic plates and aren't related.

Back-to-back earthquakes aren't all that rare, Slate Reports:

Ritsema says magnitude 7 earthquakes similar to what struck Japan happen around the world about 15 times a year (a fraction of the more than 1.4 million smaller earthquakes that occur every year). Despite this near-monthly frequency, we tend not to hear about these larger quakes—because they don't affect people all that often.

Similarly, 7.8-magnitude earthquakes like the one that struck Ecuador (killing at least 350 people and causing billions of dollars' worth of property damage) occur less often, but even they are not that rare, statistically speaking. Ritsema says they take place on average about once every one or two years. Again, many occur in areas where they cause little noticeable damage.

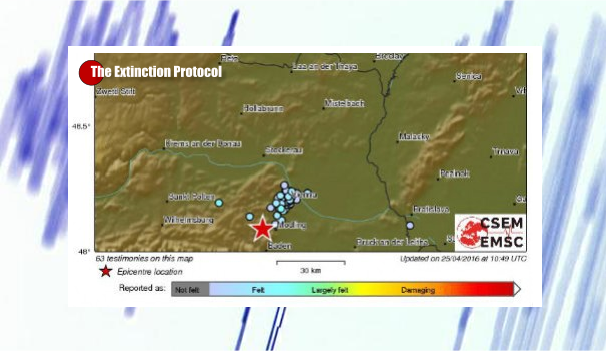

"Sometimes these events are in the middle of the ocean, far from population centers," he says. "We detect them. We see them. We record them very well. But they don't hurt anybody so they go unnoticed by the general public."

Ritsema says that one specific factor influences an earthquake's destructive qualities even more than its magnitude: "Location, location, location." What was unusual this week was that both quakes happened in fairly densely populated areas. As a result, they affected a large number of people and drew the attention of the world.

"There's nothing in the past week that indicates a change in terms of large-plate tectonics," Ritsema said. "The Earth hasn't changed. This is normal Earth behavior. If you look at the long-term catalogs for earthquakes over spans of years, there's nothing really telling us that this is a cluster of events. It's just statistics."

OK. Fine. But that magnitude-9 monster is still waiting to attack the Northwest, so some of use are going to keep hoarding cans of peaches and cream corn in our basements.

— Joseph Rose

503-221-8029

jrose@oregonian.com

@josephjrose

Last edited by Carol on Fri Apr 29, 2016 9:22 pm; edited 1 time in total