"What Are We Gonna Do Now??!!"

"When in Danger!! When in Doubt!! Run in Circles!! Scream and Shout!!"

Last edited by orthodoxymoron on Thu Feb 11, 2016 9:24 am; edited 3 times in total

Re: United States AI Solar System (1)

Re: United States AI Solar System (1)

Re: United States AI Solar System (1)

Re: United States AI Solar System (1)

Re: United States AI Solar System (1)

Re: United States AI Solar System (1)

Re: United States AI Solar System (1)

Re: United States AI Solar System (1)

Re: United States AI Solar System (1)

Re: United States AI Solar System (1)

Re: United States AI Solar System (1)

Re: United States AI Solar System (1)

Re: United States AI Solar System (1)

Re: United States AI Solar System (1)

Re: United States AI Solar System (1)

Re: United States AI Solar System (1)

magamud wrote:

Thank-you magamud and Carol. Young Orthodoxymoron Unveiled!!!Carol wrote:

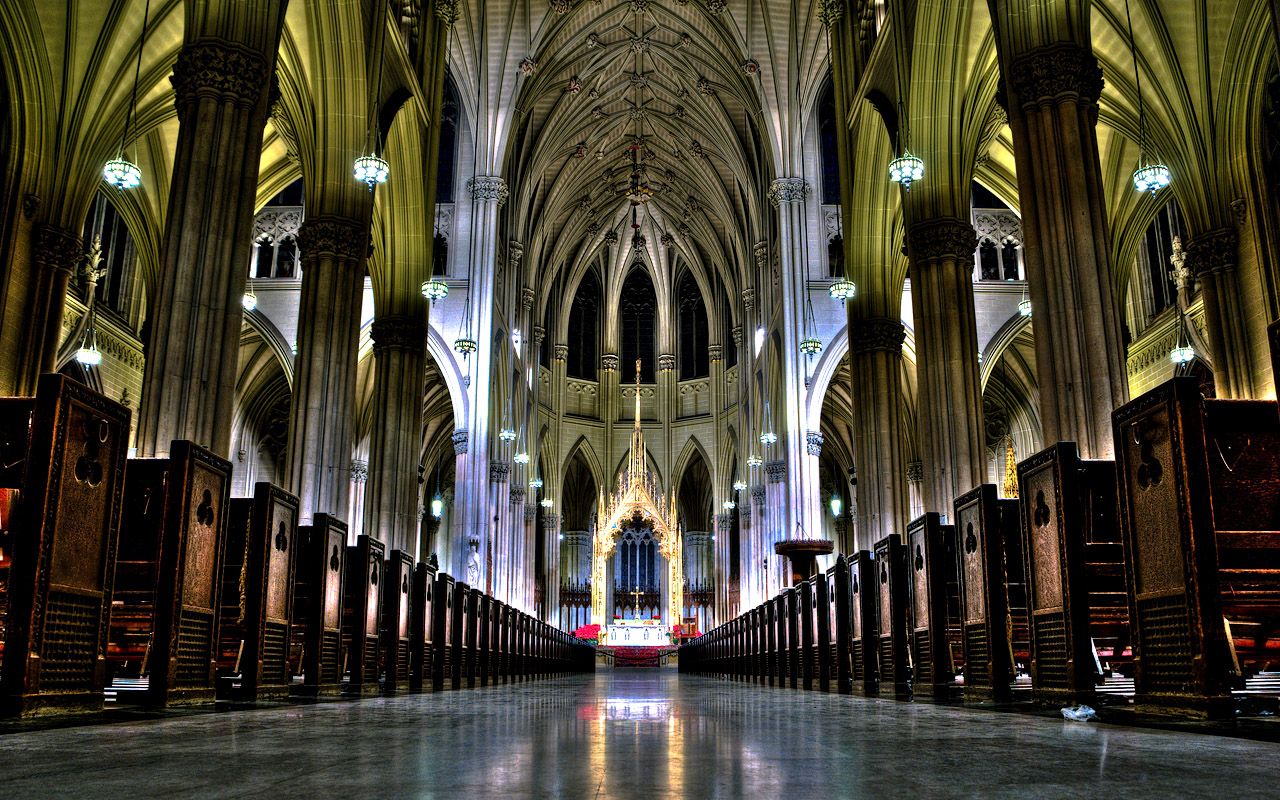

Thank-you magamud. The Mean Queen Theme is sort of cool -- yet sort of cruel. What about a Super Lady Diana as a Model Solar System Queen??!! Sorry if that offends -- but just think about THAT for a while (once your blood-pressure returns to normal). I like St. Patrick's Cathedral in NYC -- but I worry about what I keep hearing concerning various Cardinals -- and regarding what allegedly goes-on beneath Many Cathedrals (or behind locked-doors). I was just reading in Tom Clancy's Sum of All Fears (on page 22) where he refers to Cardinal Spellman as being the Catholic Vicar General of the United States Military (or something to that effect -- I don't have the book with me). I love Roman Catholic Pomp and Circumstance (even though I'm not supposed to as a Protestant) and I am intrigued by Vatican Intrigue -- but the REALLY Nasty Stuff Connected with Rome -- past, present, and future -- DEEPLY Troubles Me...magamud wrote:Thats a good one. Attorney queen.Reptilian-Human Nazi-Mason-Jesuit Agent-Attorney-Queen

That too...or have we been Manipulated and Corrupted on a Massive and Unfathomable Level so as to create a Designer-Purgatory which Maximizes Off-World Profit and Development?

Lets pray...

magamud wrote:

I should relax more before reading your posts. Here is a 4 hour picturesque harmonic relaxation video. Over 7 million hits!

Vicar general

past, present, and future -- DEEPLY Troubles Me...

Lets look at great Chasms....

Re: United States AI Solar System (1)

Re: United States AI Solar System (1)

Re: United States AI Solar System (1)

Re: United States AI Solar System (1)

Re: United States AI Solar System (1)

Re: United States AI Solar System (1)mudra wrote:Laura Magdalene Eisenhower: ET invasion has already occurred and governments do not want us to know

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OdfIuTm2VuM

Love Always

mudra

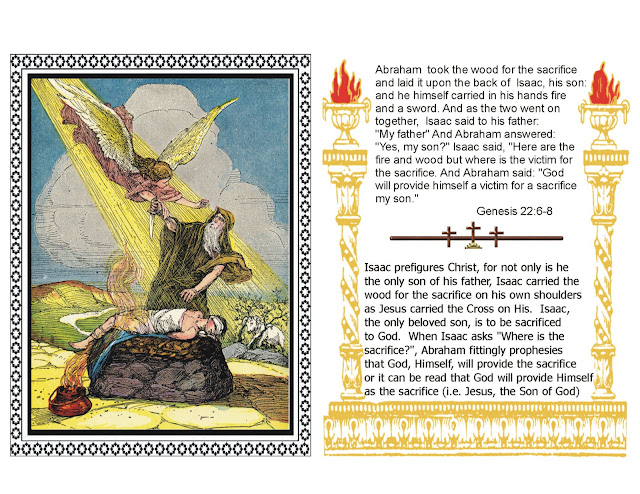

magamud wrote:I like these two, but they lose the truth when they don't acknowledge the Messiah. They believe this is a Lucifer trick and then put their "Faith" into the Goddess and benevolent ET's. And they have quite the detailed architecture about it and use empathy to reinforce it. Im not judging them, its where they are in their power and evolution. What happens is people see what they want to see. They can't see Gods entire plan and how the cosmos really works with The Father, the son and the holy ghost. So "their" story is mixed with half truths, because they are good people.

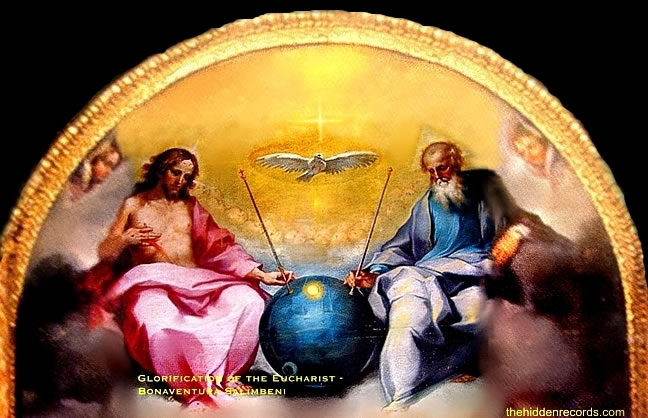

Its very simple. Lets try to concept it. There are 3 levels. There is the Kingdom. This is where truth reigns and light emanates from. Then there is the Cosmic realm. This is where ET's of all levels exist, mystics, avatars and any kind of inter dimensional beings. Then there is the Mortal plain which we are on in Earth. The dynamics with the Mortal plain and the Cosmic plain are the same. To understand Good and Evil. Its just the manifestations are different due to the variance in paradigms. What these two are in is following the Cosmic drama of the timeline without knowing how the kingdom works with it. So they are getting involved in Cosmic co dependence which benevolent ET's definitely don't want. They are trying to evolve too. And this points to the meaning of the Son of god or the Messiah. The Messiah brings all realms together every once in a while or cycles or harvests. He brings equality, transparency and shows the truth of existence.

People are very shortsighted with the power of God. He never at anytime left you alone or our collective. This is why he controlled the timeline with his prophets and gave us his Son and gave us Prophecy. And god knows whatever he controls, will be exploited by Lucifer and his Legion, as to why he only does as little as possible and lets people choose for themselves, so they can grow in their own power. This is the nature of Existence and growth in consciousness. Godspeed people.

I hate to keep talking about my encounter with one who claimed to be a particular Ancient Egyptian Deity. I don't know who they really were -- but they were very smart, very tough, and somewhat sinister. They frankly scared me -- and they made me think they might've been close to the Top of the Pyramid (either directly, or as an ambassador). They made me think that we might not be dealing with Kind and Loving Gods and Goddesses. I sometimes joke about Nazis, Masons, and Jesuits -- sometimes as being three facets of one faction. But what if it takes Bad@$$ SOB's to run a solar system in a really violent and nasty universe!! What if we're really dealing with Zionists and Teutonic-Zionists at the highest levels of solar system governance?? I keep imagining a Really Bad@$$ War-Room at the center of solar system governance -- with some really frightening individuals (human and otherwise)!! I've joked about being a Token Nice-Guy Insider -- but just thinking about this makes me feel incredibly guilty and dirty. I get the feeling that it might be VERY Difficult to remain Good at the Top of the Pyramid. When I joke about a Reptilian-Human Nazi-Mason-Jesuit Agent-Attorney-Queen -- I'm Really NOT Joking!!!orthodoxymoron wrote:I'll watch the video later today -- but I just wish to say that I am very paranoid regarding governance -- micro or macro. How does one determine who is REALLY in the Driver's-Seat -- and whether they are good for this civilization, or not?? Further, how do we know that we know anything about anything, with a high degree of certainty?? I lean toward Judeo-Christianity -- but there are literally hundreds (or thousands?) of versions of what that is, exactly. I keep providing study-lists regarding Judeo-Christianity -- but no one seems to notice. Who REALLY wrote the Bible -- and under what circumstances?? I am not at peace with the Bible. I have HUGE problems with human-sacrifice and mass-murder -- which are central to the substitutionary-atonement and apocalyptic-salvation. I keep wondering if Malevolent ET has been ruling humanity for thousands of years -- with other Malevolent ET Factions waiting for their turn to have their way with humanity. Talk of a Regime-Change doesn't exactly make me jump up and down with joy. It might take Bad ET to defeat Bad ET!! But then we're still stuck with Bad ET!! I'm seriously considering studying Intergalactic-Banking and Star-Warfare (as stupid as that sounds)!! I am VERY disillusioned regarding life, the universe, and everything.

orthodoxymoron wrote:Thank-you magamud. What you wrote gets at the heart of a theory of mine. "The only real technology is nature. I suspect as we use entertainment for voyeurism to process our unconscious, other worlds use us, in the same way. Since our species cannot see, it is used like a hub for other species to play out their unconscious. They keep it unconscious, because it is believed this will forgo their responsibility. This is of course a great fallacy and what experience, evolution and awareness is all about." What if Earth-Humanity is a Fallen and Sinful Illegal-Creation in Lockdown?? What if the confusion, misery, and forbidden-pleasures of this dark world have somehow developed the souls in this solar-system in good and bad ways -- with the net-change being in the positive direction?? But what if the rest of the universe has been corrupted by watching this Theater of the Universe aka Theater of the Absurd?? "By beholding we become changed." What if Earth-Humanity has been a desperate and dangerous experiment -- designed to accelerate the evolution of the universe?? I have suggested the possibility of a very Ancient, Traditional, and Violent Other-Than-Human Universe -- with Earth-Humanity being a "Fly in the Ointment." I continue to feel as if I am in profound conflict with Divinity, Humanity, and Myself -- regardless of whether I wish to be, or not. I have been hinting at a very structured and organized responsible-democracy under the guidance of a benevolent minimalist-theocracy aka The United States of the Solar System. One would probably have to study this concept for decades to really "get it". I don't think I "get" my own internet posting. It might really require 122 years to properly analyze and implement such a concept. If it were presently dumped upon this solar system -- things might REALLY go to hell. I am extremely apprehensive regarding Disclosure-Events, Regime-Changes, and Apocalyptic-Salvation. The Revolutionary-Evolution of this Solar-System might get unimaginably nasty. If there were an all-out Solar-System Final-Jihad -- there might be nothing left -- nothing but one big asteroid-belt mixed with space-dust -- and I wish I were kidding. I've been told that we've done better than expected -- that things have worked-out well for humanity -- but that things continue to worsen -- and that I don't want to know what deals and treaties exist at the highest levels of this solar system. I've been told that humanity should never have been created -- and that we need to start over. I've been told that a Leader of Humanity will fail -- which will be followed by an extermination. I've heard that God was (and is?) prepared to start-over (regarding humanity) rather than change the way they govern the universe. Physicality and Governance seem to be the Key-Issues. Consider the concepts of Absolute-Ethics and Absolute-Obedience relative to Human-Nature, Divine-Sovereignty, and Responsible-Freedom. Consider reading the Bible (from cover to cover -- straight-through) in the context of Science-Fiction. Once again -- I'm not out to screw anyone or anything. I simply wish for things to work out well for all-concerned. Here is one more study-list (with scripture preferably in the KJV):

1. Patriarchs and Prophets by Ellen White.

2. Isaiah.

3. Matthew.

4. Job.

5. Mark.

6. Psalms.

7. Luke.

8. Proverbs.

9. John.

10. Ecclesiastes.

11. Acts.

12. The Desire of Ages by Ellen White.

13. The 1928 Book of Common Prayer (and Liturgy).

14. The Music of J.S. Bach.

15. The Gods of Eden by William Bramley.

16. The Federalist Papers (with US Constitution).

17. Astronomy Textbooks.

18. Science Fiction.

All of this has as much to do with mental and spiritual conditioning as it has to do with any perception or conviction regarding absolute truth. Continue to focus upon Ethics, Law, Law-Enforcement, Governance, Spirituality, Physicality, Business, and Church-State Issues.

Re: United States AI Solar System (1)

Re: United States AI Solar System (1)It is what it is...It seems as if one must sleep with the devil to get anywhere in this god-forsaken world

If there weren't I would not think you sane. The question is can you find Gods love in the narrative. Do people even want to? There is so much mysticism or atheism to tempt you. Godspeed Ortho...There are even some aspects of Judeo-Christianity which seem quite dark to me.

Re: United States AI Solar System (1)

Re: United States AI Solar System (1)

mudra wrote:orthodoxymoron wrote:I'll watch the video later today -- but I just wish to say that I am very paranoid regarding governance -- micro or macro. How does one determine who is REALLY in the Driver's-Seat -- and whether they are good for this civilization, or not?? Further, how do we know that we know anything about anything, with a high degree of certainty?? I lean toward Judeo-Christianity -- but there are literally hundreds (or thousands?) of versions of what that is, exactly. I keep providing study-lists regarding Judeo-Christianity -- but no one seems to notice. Who REALLY wrote the Bible -- and under what circumstances?? I am not at peace with the Bible. I have HUGE problems with human-sacrifice and mass-murder -- which are central to the substitutionary-atonement and apocalyptic-salvation. I keep wondering if Malevolent ET has been ruling humanity for thousands of years -- with other Malevolent ET Factions waiting for their turn to have their way with humanity. Talk of a Regime-Change doesn't exactly make me jump up and down with joy. It might take Bad ET to defeat Bad ET!! But then we're still stuck with Bad ET!! I'm seriously considering studying Intergalactic-Banking and Star-Warfare (as stupid as that sounds)!! I am VERY disillusioned regarding life, the universe, and everything.

Oxy to me the real thing to fear is our own thoughts for freedom begins with our state of mind.

Love for You

mudra

orthodoxymoron wrote:Thank-you, mudra. In Communist-Russia and Nazi-Germany -- one might legitimately harbor fear and paranoia. They really might be out to get you -- especially if one were critical of the government. I understand inner-peace -- yet I also understand facing-reality and acting-responsibly.

Thank-you mudra. I guess I'm dealing with some heavy-duty modeling and speculation -- which involves Angry and Jealous Gods -- who might meet me on the 'other-side' with unimaginable harshness -- especially in light of what I've posted on this website. It almost seems as if considering all possibilities, and solving the world's problems, is viewed with suspicion and scorn -- consequently placing one on multiple agency lists -- as a threat to who knows who and/or what. What's really scary to me, is that I seem to be getting more understanding and sympathetic toward the powers that be (human and otherwise)!mudra wrote:orthodoxymoron wrote:Thank-you, mudra. In Communist-Russia and Nazi-Germany -- one might legitimately harbor fear and paranoia. They really might be out to get you -- especially if one were critical of the government. I understand inner-peace -- yet I also understand facing-reality and acting-responsibly.

Inner peace to me is about knowning without an inch of a doubt that your are soul , that you are Spirit so that when adversity comes and death is maybe your last experience on the line mind does't have you believe that this is the end. A confused mind is like a veil on Spirit. Your body maybe shivering in fear but who you really are, HeartSoul, is'nt stopped by that. On the contrary HeartSoul takes command and faces whatever there is to face with full responsability for it knows well that life is more. There is no contradiction there Oxy.

Love from me

mudra

Re: United States AI Solar System (1)

Re: United States AI Solar System (1)orthodoxymoron wrote:Thank-you Beren. Your kind counsel is always welcome -- and you have pointed-out that I am a confused-soul several times. I am still awaiting a detailed critique of my internet activities. I applied for an NSA FoIA half a year ago -- with no results. Are you pleased with the history of this solar system and its inhabitants?? Are the inmates well-behaved?? Has the insanity been well-managed?? Are you proud of yourself -- and satisfied with your mental and spiritual progress?? Namaste.Beren wrote:orthodoxymoron wrote:I will continue to say that I'm at war with humanity -- at war with divinity (the management of humanity -- which might be middle-management) -- and at war with myself. The whole thing stinks -- and even though I keep conceptualizing idealistic solutions -- I fear that things might get a lot worse before they get better -- if they get better.

Ortho,

maybe you need to see who is activating your personal energy so that you act like a ping pong ball-here and there .

I am saying this with all sincerity and care.

You write and spare a lot of energy on too many ideas.

It sounds like a confusion my friend.

In ultimate reality all is possible even here though consciousness to realize this is limited now.

I see you as a good soul though a bit confused sometimes.

But an awesome library of knowledge is within you, just focus! :)

Re: United States AI Solar System (1)

Re: United States AI Solar System (1)

Thank-you magamud. I continue to be very conflicted regarding the human predicament -- and regarding various definitions and interpretations of this and that. What is a 'Demon'? What is 'Sin'? Is the 'New World Order' fundamentally evil -- or is the NWO fundamentally mismanaged? Things can appear to be a certain way -- but changing just one key factor can change the whole nature of the beast. I will look at the videos later today. I continue to think that the more power one has -- the more likely it is that they will become corrupted and deranged. My Political and Theological Science-Fiction continues to scare the hell out of me each and every day. I feel corrupted and deranged just by thinking about solar system governance. I continue to be intrigued by the concept of Absolute-Access with Absolutely Zero-Power. This is an application of the Combining-Opposites Principle. I'm trying to think of various and sundry possibilities and probabilities regarding how the solar system might really work -- and regarding what might go terribly wrong. I continue to think that Plum Solar System Jobs should NOT be that desireable. I continue to think that the solar system is managed as a Big Business -- which might not be such a bad model -- provided that no one (human or otherwise) gets misused, abused, hurt, or killed. Solar System Governance might, of necessity, have to be somewhat harsh and arbitrary -- but without becoming unethical and violent. A while ago, someone commented to me that it would've been better to have left everything in the Lord's Hands -- and I'm not sure what they meant by that. Having the Right Lord would be extremely important. I'm also intriqued by the suggested connection between Christ and Satan. If my 2,300 day-year prophetic theory is even somewhat correct concerning Daniel 8:14 -- that it spans 168BC to 2133AD -- how might this affect the way we think about solar system governance?? Thinking about all of this seems to be a HUGE waste of time. I often feel like Pinky or the Brain -- I'm not sure which. Perhaps I should just think about things like this: 1. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4lnPIt3mU8Q 2. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4x9QIt_fqQE 3. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uHTua_Q8CL0 4. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MtA_6lIhKWY 4. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pV1M0mIniJg 5. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ueU4CDjn3v0 6. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xt5Qsyg2mFQ Wanting to be a Wannabe-Somebody is SO Overrated. We should be happy right where God has placed us -- or so I am told. I really just want things to make sense and work well. I will continue to think that This Present Madness is a Corrupted Idealistic Plan which simply needs to be purified and refined. Good-luck with that -- right??!! I really think such an effort might not be completed until 2133AD. Then, at long-last, the Sanctuary might be finially cleansed, vindicated, and restored to its rightful state. Perhaps this is something to look forward to in my next two or three lives...magamud wrote:New World Capitals 1:00:00

Published on Dec 1, 2012

http://freemantv.com/ Preplanned cities designed as magical seals for controlling demons are on the rise. Are we witnessing the creation of the New World Order capitals?

magamud wrote:Great links thx O. Nothing like pipes to clean out the air.

I see a lot of double edge sword stuff, two sides of the coin, yin and yang, yadda, yadda stuff. Perhaps its good one has a sword, a shekel, an esoteric term? I think the "Fruits" of evil magnetize the fruits of good to come on in to acknowledge the whole. The A.I. machine efficiency brings in the yangs wang to thrust all this mega goop outta here? As to why they enjoy savoring the moment? Now thats Irony and time travel and the essence of Fate. Good always triumphs evil? The myth lives in Wormwood and every other million prophecies that every good man has tried to warn the planet about. Freewill has a consequence. And what is the price of Liberty? A meat sack body? An Eden? How long shall life support idiocy?

The idiocy has hollowed out our matrix like cancer. The illusion is a house of cards...

No one knows except the Father when he returns. Like your mortality, it is the way of things. Big deal or not?

Largest Pipe Organ in China

I am coming quickly...

Re: United States AI Solar System (1)

Re: United States AI Solar System (1)

Re: United States AI Solar System (1)

Re: United States AI Solar System (1)mudra wrote:New Colonel Philip J. Corso Info Surfaces! - US Gave Russia Advanced Technology To Stop WW3!

William Birnes of the History Channel revealed in our recent interview that Colonel Philip Corso of "Day After Roswell" fame stated we almost went to war with Russia and that conflict was settled because somehow, the USA gave the Russian Government the technology for the Russian Mig Fighter Jets Radar systems during our interview I have shared here. (dead-link)

Love Always

mudra

Take a very close look at the Entire Life of Colonel Philip J. Corso. His son has said some very interesting things about Colonel Corso (which I have noted elsewhere in this thread). I tend to think that we have a very complex and nasty factional conflict raging in this solar system (which we won't be told about on Fox News)!! I suspect that all factions are mixtures of good and evil -- and I guess I've been conceptualizing a constructive resolution of the War in Heaven -- but don't hold your breath.orthodoxymoron wrote:Some say that all of the advanced military-technology and weapons-systems throughout the world (and throughout the solar system??) are owned and operated by ONE Group or Individual. This is frightening for me to think about. If all of the nasty weaponry were not centrally controlled -- we might've blown ourselves up a long time ago. OR -- we might've long since been blown to Kingdom-Come by ET. However -- what if Humanity has been working for Bad-ET for thousands of years -- which might include building a Kick@$$ Space-Fleet for Bad ET (and NOT for Humanity)??!! But what if said Bad-ET is better than the rest of the Bad-ET Factions throughout the universe??!! What if Humanity Lives in a VERY Tough Neighborhood??!!

Re: United States AI Solar System (1)

Re: United States AI Solar System (1)

Re: United States AI Solar System (1)

Re: United States AI Solar System (1)

magamud wrote:Fantastic posts O....

Afraid of the Dark?

Re: United States AI Solar System (1)

Re: United States AI Solar System (1)What continues to amaze me is the gratuitous-violence in movies, video-games, and television -- which seems to be fine -- and given a pass -- while the most trivial and innocent things are cracked down upon!! I've experienced some of this madness first-hand!! It's as if they WANT All Hell to Break Loose -- so they can REALLY crack down!! It seems as if they brain-wash the people with violence in the mass-media -- and then antagonize them in real-life -- to create a perfect-storm of discontent -- just waiting to be explosively-ignited by some planned 'unforeseen' event!! It wouldn't surprise me if those who are tasked with 'cracking-down' eventually 'crack-down' upon each-other as the heat keeps getting turned up!! The people need to remain cool, calm, and collected -- no matter what -- and just keep exposing the crime, corruption, murder, and mayhem. It wouldn't surprise me if the current New World Order Powers That Be are replaced by more ethical and competent New World Order Powers That Be -- with a fine-tuning and responsible-reformation of the Way Things Are. I continue to suspect that this world is a corrupted-version of an idealistic-plan. Think of the contrast between Renate Richter and Klaus Adler in Iron Sky!! Just a Thought.Jenetta wrote:Published April 18th/2014

As the government continues down their path of oppressive tactics in order to ensure a compliant population, the Obama administration has recently recruited the helps of all parents alike in the search for domestic terrorism. The only problem is that the government claims that parent’s own “confrontational” kids could be the source of potential American destruction.

The news comes directly from the White House where White House counterterrorism and Homeland Security adviser Lisa Monaco expresses the need for parents to keep and ever-diligent eye on their children. Monaco urges parents to monitor closely for “confrontational” behavior as it may be indicative of future terrorism.

In effort to spread the panic a bit more, she even went so far as to insist that parents watch for, “sudden personality changes in their children at home.” Despite puberty probably being the largest contributor to such an outcome, the government remains adamant in their directions.

After hypothetically asking exactly what parents should look for, she answered her own question by stating, “For the most part, they’re not related directly to plotting attacks. They’re more subtle. For instance, parents might see sudden personality changes in their children at home—becoming confrontational.”

Recruiting parents as their own surveillance agents, Monaco explains that, “the government is rarely in a position to observe these early signals.” Expressing the need to seek out, “homegrown extremism,” as soon as possible, parents play a crucial role in the identification of terrorist children.

Since Obama has taken office, the government agenda to transform the definition of “domestic terrorism,” has become somewhat of a priority. Including characteristics that cover much of the population, it seems that those being deemed the most dangerous are coincidentally the direct opposition to the left.

Proving that those who don’t agree with the progressive agenda are unfairly being labeled terrorists was Harry Reid just yesterday. Declaring that the anyone in support of Nevada rancher Cliven Bundy was effectively a, “domestic terrorist,” their agenda has become transparently clear.

Giving just one last hard-hitting example of government bias, Infowars reports, “A Homeland Security study leaked in 2012 upped the ante even further, demonizing Americans who are “suspicious of centralized federal authority,” and “reverent of individual liberty” as “extreme right-wing” terrorists.”

One can only speculate that as the government shifts its focus upon American citizens, it leaves our beloved country vulnerable to potential foreign attacks. Despite this being the case, it appears that the government is more worried about remaining in control rather than not initiating a civil war.

What do you guys think – is this ridiculous? And what does it say about the current state of our government? Let us know in a comment below.

http://tellmenow.com/2014/04/obama-administration-warns-confrontational-kids-are-terrorists/

__________________________________________________

As it is below; so it is above

Re: United States AI Solar System (1)

Re: United States AI Solar System (1)

Re: United States AI Solar System (1)

Re: United States AI Solar System (1)Thank-you magamud. I look closely at everything you post -- but I don't necessarily comment on everything. What worries me is that we might not live in a nice and peaceful universe -- and that the creation of humanity was an attempt to make things better -- which isn't working. What if this solar system is such a mess that NO ONE can make it better -- regardless of whether they are good, bad, human, or otherwise??!! I know we've been lied to -- and stolen from -- but what if some of what seems to be reprehensible has been necessary -- on some abstract level??!! What if a Reptilian-Human Nazi-Mason-Jesuit Agent-Attorney-Queen presides over a Reptilian-Human Nazi-Mason-Jesuit Galactic-Empire??!! If true -- what if such a state of affairs is simply the way things work -- regardless of whether we like it or not??!! What if we are stuck with a Queen A (Gabriel?) v Queen B (Michael?) v Queen C (Lucifer?) Galactic Star War in Heaven??!! What if the Nice-Queen quickly becomes the Mean-Queen once they Gain the Reigns -- and Reign??!! What if Politics and Religion as We Know It are a necessary cover for some Really Nasty Politics and Religion as We DON'T Want to Know It??!! I keep joking about becoming some sort of an insider in a future-life -- but I doubt that this would make me happy -- or that it would make things better. We might simply be VERY lucky if things don't get a helluva lot worse. We might be lucky to simply survive. I will continue to positively-reinforce and positively-rearrange that which presently exists within this solar system -- in my imagination and within this website -- even though it will probably be an inconsequential exercise in futility. I will continue to conceptualize Ancient Egyptian Deities in Conflict Within This Solar System -- regardless of whether this is the case or not. It's getting much more difficult to keep secrets and cover things up in the internet-age. In a way this might be good (for cleaning-up corruption) -- but in another way it might be bad (by informing us how bad things really are -- and consequently driving a lot of us insane).magamud wrote:

Here's another variation on my Biblical Study List:orthodoxymoron wrote:The more I think about prophecy, the more I agree with what you just said, Mercuriel. God, Satan, Lucifer -- or Somebody -- seems to have been making this solar system exactly the way they have wanted it to be -- rather than just a bunch of stupid-humans getting in each others way. I'm not celebrating the resignation of the Pope. I wouldn't celebrate the resignation of the Queen. I wouldn't celebrate the resignation of the President. We'll still be faced with the same Underlying Bullshit. What worries me is that we might not be able to escape the darkness which exists -- not just in this solar system -- but possibly throughout the universe. This view is completely opposite of what I grew-up believing -- but my faith has been BADLY Shaken -- and I don't see much chance of regaining my faith during the remainder of this incarnation. I just read an article in The Wall Street Journal about a Jewish Hedge-Fund Manager who is an Atheist -- yet collects rare and expensive Jewish Ceremonial Items. I get the impression that there are a lot of people in this category. They're not buying the traditional-story -- but they still need a sense of identity which comes from some sort of association with religion. I guess I'm sort of a New-Age Happy-Clappy Anglican-Adventist-Agnostic -- who is (as Beren keeps pointing-out) quite confused.Mercuriel wrote:Brook wrote:Why would a Pope canonize a Saint that would predict the demise of not only the Church and seat of the Pope itself...but most notably seat the Antichrist ?

Only If It was planned like that way back then My Dear Sister - Only if It was planned that way...

Simply put - Its not so hard to predict or prophesy something especially if one has the control necesary to MAKE SURE It occurs...

Re: United States AI Solar System (1)

Re: United States AI Solar System (1)

Re: United States AI Solar System (1)

Re: United States AI Solar System (1)

Re: United States AI Solar System (1)

Re: United States AI Solar System (1)